I’ve had an astonishingly ‘crafty’ summer. Plus, there’s work (bechod) and, what with one thing and another, blogging has taken a bit of a back seat. But I’ve still been brooding on fulling. I realise lots of people will know all about this, but I didn’t. Well, I knew bits, but only bits. I didn’t realise, for instance, that urine had ever been taxed and, quite apart from why, how? I have to admit that I still don’t understand the fiscal process. How on earth do you tax pee?

Ahem. Fulling cloth – kneading the woven cloth until the fabric thickens as the threads felt and close together, while also cleaning it – was one of the earliest cloth-making processes to be mechanised, but that wasn’t until the early middle ages. Before that it was largely down to feet.

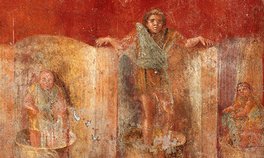

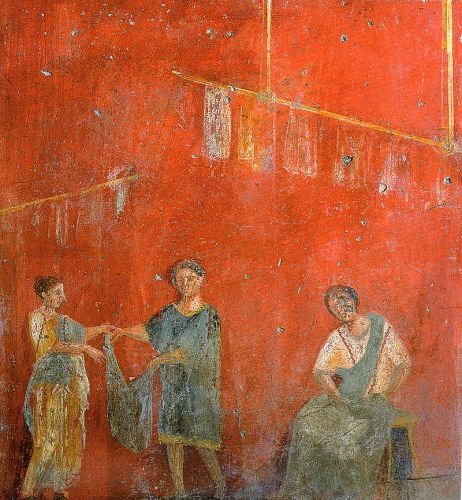

Roman fulleries had their slaves treading away in booth-like structures, and similar processes – often called ‘walking’ (Ireland and Wales) and ‘waulking’ (particularly in the Hebrides) – have persisted as part of a commercial process almost into the present.

Roman fulleries had their slaves treading away in booth-like structures, and similar processes – often called ‘walking’ (Ireland and Wales) and ‘waulking’ (particularly in the Hebrides) – have persisted as part of a commercial process almost into the present.

There can seem to have been an excess of fullers in some Roman towns, but that’s probably down to a form of sampling bias. A fuller’s workroom / shop is one of the easiest places to recognise, which may make them seem more prominent than they might have been at the time. Maybe. Probably not, though: Romans did not wash their clothes (or anything else made of cloth) at home. Fulleries are completely distinctive, with their booths, vats and large sinks.

Few trades leave clearer traces behind them:

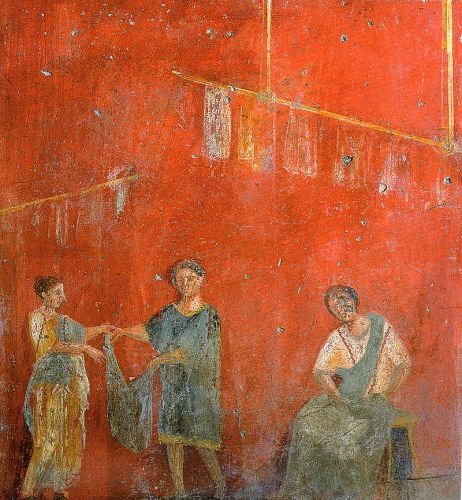

Fullers (preparing cloth before it went into use) and laundries (not just cleaning cloth but often refurbishing it too) generally seem to have been the same place. Fullers, with common Roman snobbery towards the ‘working classes’, were a source of amusement to the elite, and Cicero’s detractors often teased him with being the son of a laundry owner. Fullers might also have been part-timers; one piece of Pompeiian construction graffiti states that ‘Mustius the fuller did the whitewashing’ – so he clearly had a sideline, or maybe he was moonlighting to make ends meet. Also in Pompeii is a house with an ‘oversized’ dining room which had a lot of graffiti celebrating fullers; Mary Beard has suggested (in Pompeii) that it might have been where they went for after-work drinks, and why not?

It was a smelly trade, though, which makes the fact that fulleries could be next to elegant houses rather surprising, to us. It was pongy because of the importance of pee in the cleansing process, and that is why the emperor Vespasian taxed human urine – it was a levy on the textile industry, and specifically on the fullers; nicely stale urine was a source of ammonium salts which helped to whiten the cloth. It was collected in large clay pots which were placed in strategic locations – outside shops, public urinals, road intersections (!) – though the fullers deliberately avoided some, notably the pots outside inns. That’s because post-piss-up pee is lower in nitrogen and not so effective. The things you learn.

First, the fabric was soaked in a heated mixture of old urine and water in a fulling stall, and then the fullers – or more likely the slaves – would go into the stall, rest their hands on the sides and start stamping. Once the fulling process was complete the fabric was thoroughly rinsed (thank heavens), wrung out (took at least two people; a toga could be nearly 7 metres long) and then spread out over frames to dry. Once dry, the nap was raised by using thistle heads, and then trimmed to a constant height using ‘cropping shears’, which are often represented on gravestones.

Incidentally, there is evidence that any dyeing often took place before weaving the cloth, which is probably not surprising given how throughly the finished fabric was worked afterwards. The effectiveness of the fulling process can be seen in reports of the spotless white togas of senators; they were woollen, and – naturally – subject to this process for cleaning as well as finishing the cloth in the first place.

If you were of more humble status your clothes were more likely to be dull and brownish rather than white, largely because they would not be so expensively produced or laundered. Harriet Fowler (in Women of the Roman Republic) thinks they may have been produced / cleaned separately, probably in different establishments, which seems highly likely to me – you’d probably be using less of the taxed constituents, maybe watering them down more, if you were doing it for people who couldn’t afford much. There were different types of fulleries: broadly, small local ones, often near market places, and huge imposing ones which clearly had many more workers / slaves. Bigger, smarter places for those who could afford them? Also highly likely, I think. (The parallels between the Roman world and our own just get stronger and stronger – for instance, they had their celebrity chefs and obscure equivalents of things like birch-sap reductions too). And, just as a final note, the slaves who did the treadling did so in bare feet.

Moving on, rather hastily, to Wales, though the stained glass with a fuller treading away at top left comes from France. The other panels are the next stages of cloth finishing, too.

Moving on, rather hastily, to Wales, though the stained glass with a fuller treading away at top left comes from France. The other panels are the next stages of cloth finishing, too.

It may seem that Ancient Rome and Mediaeval Wales have not got that much in common (apart from some vocabulary the Romans left behind, now preserved in the Welsh language), but fulling, as elsewhere, is one thing: the fact that it was almost the only part of the textile production process which not done at home. Prepping fibre, spinning, weaving: yes, all done in your home (or in the home in which you worked as a domestic servant). Fulling: nah. Not surprising, really, even when Fuller’s Earth was being more frequently used. Fulling still involved a lot of stamping about in – well – stale piss. Or it did, for a considerable time. And then came fulling stocks, which must have been a relief….

Main source for Rome: Miko Flohr, The World of the Fullo, OUP, 2013. Wales next (and this time without a gap of several weeks!)

Roman fulleries had their slaves treading away in booth-like structures, and similar processes – often called ‘walking’ (Ireland and Wales) and ‘waulking’ (particularly in the Hebrides) – have persisted as part of a commercial process almost into the present.

Roman fulleries had their slaves treading away in booth-like structures, and similar processes – often called ‘walking’ (Ireland and Wales) and ‘waulking’ (particularly in the Hebrides) – have persisted as part of a commercial process almost into the present.

Moving on, rather hastily, to Wales, though the stained glass with a fuller treading away at top left comes from France. The other panels are the next stages of cloth finishing, too.

Moving on, rather hastily, to Wales, though the stained glass with a fuller treading away at top left comes from France. The other panels are the next stages of cloth finishing, too.

We’ve all got fleeces, I bet. I have – had – a fleece throw which went on the bed when it got cold. I’ve got a couple of hats, gloves I wear when scraping ice off the car, a crappy garden fleece, a walking fleece, an almost smart fleece – and that’s even though I’m a knitter and spinner. They’re handy. I keep one by the door, chuck it on when I go to get logs. And not as bulky as a big sweater, either. Nice and light. But what are they made of?

We’ve all got fleeces, I bet. I have – had – a fleece throw which went on the bed when it got cold. I’ve got a couple of hats, gloves I wear when scraping ice off the car, a crappy garden fleece, a walking fleece, an almost smart fleece – and that’s even though I’m a knitter and spinner. They’re handy. I keep one by the door, chuck it on when I go to get logs. And not as bulky as a big sweater, either. Nice and light. But what are they made of? The fibres are spun together, and collected onto huge spools. They are then mechanically knitted on a circular knitting machine into an enormous tube. Fleece is, of course, fuzzy. That’s because the resulting material is then fed through a ‘napper’ which raises the surface, and then to a shearing machine, which cuts the fibres – as in the manufacture of, say, velvets. The resulting fabric is then finished (if necessary), which can involve spraying it with waterproofing or fire retardant or something to set the texture. This could have been the source of my dermatitis.

The fibres are spun together, and collected onto huge spools. They are then mechanically knitted on a circular knitting machine into an enormous tube. Fleece is, of course, fuzzy. That’s because the resulting material is then fed through a ‘napper’ which raises the surface, and then to a shearing machine, which cuts the fibres – as in the manufacture of, say, velvets. The resulting fabric is then finished (if necessary), which can involve spraying it with waterproofing or fire retardant or something to set the texture. This could have been the source of my dermatitis.

. It’s gone bonkers; it always does at this time of year but it takes me by surprise nonetheless. Everything is burgeoning. Especially weeds, and P’s dog/overgrown puppy who spends a lot of her time here digging parts of it up while looking for the chafer grubs she can hear moving under the grass, and for dahlia tubers she can’t hear do any damn thing, but which she digs up anyway. Grrr. See? Distracting.

. It’s gone bonkers; it always does at this time of year but it takes me by surprise nonetheless. Everything is burgeoning. Especially weeds, and P’s dog/overgrown puppy who spends a lot of her time here digging parts of it up while looking for the chafer grubs she can hear moving under the grass, and for dahlia tubers she can’t hear do any damn thing, but which she digs up anyway. Grrr. See? Distracting. This is sort of part of No. 2, in that I often write about food and cooking, and not just on my work-related blog; I’m working on cold soups at the mo, for instance. I get paid for it (eventually), and have just been allowed into the Guild of Food Writers. But I also enjoy cooking enormously, and it’s related to No. 3 right now – in that I have to eat what remains of last year’s produce and empty the freezers before this year’s insanely over-optimistic, somewhat hysterical, let’s admit it, plain-and-simple overproduction kicks in. I like beans but I’ve still got about two kilos left from last year. I’m growing enough spuds for a family of six. I can’t even fit the courgettes in, so they’re going to have to wait in large pots for the garlic to be harvested. Why do I do this?

This is sort of part of No. 2, in that I often write about food and cooking, and not just on my work-related blog; I’m working on cold soups at the mo, for instance. I get paid for it (eventually), and have just been allowed into the Guild of Food Writers. But I also enjoy cooking enormously, and it’s related to No. 3 right now – in that I have to eat what remains of last year’s produce and empty the freezers before this year’s insanely over-optimistic, somewhat hysterical, let’s admit it, plain-and-simple overproduction kicks in. I like beans but I’ve still got about two kilos left from last year. I’m growing enough spuds for a family of six. I can’t even fit the courgettes in, so they’re going to have to wait in large pots for the garlic to be harvested. Why do I do this?